Recent Blog Posts

October 24, 2013

Periodization in Resistance Training

In this latest episode of the B&B Connection, Bret and I discuss periodization and its relevancy to resistance training. In case you don’t know, periodization can be defined as the planned manipulation of exercise program variables (in this case sets, reps, load, etc) to optimize a given fitness component. Despite what you may have heard, research on periodization is highly conflicting. Here we discuss the limitations of the researh, delve into what can be gleaned from science as well as experience, and provide opinions for practical application of periodized principles. Hopefully it provokes thought and debate on the topic. Enjoy!

embedded by Embedded Video

October 15, 2013

Fitness Podcasts

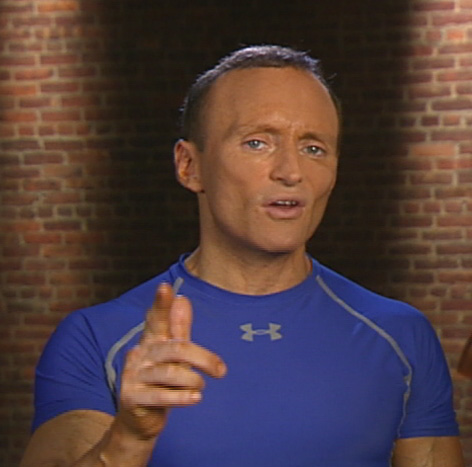

Happy to report that I’ll be doing regular fitcasts with my brother-from-another-mother, Bret Contreras, which we somewhat unoriginally call the B & B Connection (what’s in a name, right?). We’ll be discussing the practical application of research on a variety of fitness topics, objectively delving into some of the more controversial issues that currently exist. Each fitcast will be limited to 30 minutes (translation: we’ll cut right to the meat of the topic without any fluff).

Our inaugural fitcast covered the mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy. We explored my review paper, The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training, with specific emphasis on the roles of mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and myodamage on muscle development. For anyone interested in maximizing their muscle mass, this fitcast will serve as a primer to help with optimizing exercise program design.

In our second fitcast we tackled the hotly debated topic of high-intensity resistance training (HIT). For those who don’t know, HIT is a catch-all for single-set training. The discussion was spurred by a recent research study showing that single set training was equally as effective as multi-set training in improving measures of upper body strength. As is often the case, however, the devil is in the details. What does not get mentioned in the abstract (or anywhere in the discussion, for that matter), is that the “single set” group actually performed one set of three exercises for each muscle group. Given that the subjects trained three times per week, this amounted to nine sets per muscle per week. Not exactly what I would consider a “single set” routine, and certainly not consistent with what HIT pioneers such as Ellington Darden have prescribed as optimal for muscular adaptations. Understand that this by no means invalidates HIT as a potentially viable approach. As Bret and I discuss, the issue on training volume ultimately comes down to your personal goals. I highly encourage you to give this one a listen and let us know your thoughts on the topic.

Suffice to say, I’m very much looking forward to our future B & B fitcasts. Stay tuned.

In addition to my collaboration with Bret, I’ve been interviewed on a number of other sites recently. Here’s a rundown of each:

embedded by Embedded Video

Okay, gotta get back to work on my dissertation now. In the meantime, hope this provides you with enough listening enjoyment for the time being!

Brad

October 12, 2013

Reebok One Videos

As mentioned previously on this blog, I’m thrilled to serve as an educational consultant to Reebok — a world leader in fitness and sporting apparel. In my consuling role, I’ll be contributing monthly content to the ReebokOne website. Here are two recent videos I filmed for the site that you may find of interest:

The first video demonstrates an awesome variation of the traditional plank called the long-lever posterior tilt plank (LLPTP). This variation was popularized by Pavel Tsatsouline of the RKC. Research from my human performance lab shows that the LLPTP blows away the traditional plank with respect to abdominal muscle activity. It’s a challenging exercise, but for more advanced lifters definitely something to have in your training arsenal. Here’s the link: Long-lever posterior tilt plank video

The second video addresses the longstanding claim that you shouldn’t allow your knees to travel past the line of your toes when squatting or lunging. This belief has been adopted as gospel in a majority of the fitness community. Question is, does the claim have validity? Find out the real science here: Is knees-over-toes harmful during the squat?

In order to view the videos, you do need to register on the ReebokOne site. The good news is that registration is free and takes only a few minutes. Hope you enjoy the content!

Cheers!

Brad

September 27, 2013

This and That…

Lot’s going on. Without further ado…

That’s all for now. Will post again soon!

Brad

August 24, 2013

High Protein Intake: Myths and Misconceptions About Safety (Part 1)

Read pretty much any academic nutrition text and you’ll get the same-old same-old about high-protein diets being harmful to your health. The concerns center around everything from cardiovascular disease to kidney function to bone resorption. Question is, are these claims grounded in science or are they mostly hyperbole?

We can dismiss the cardiovascular claims offhand as they are based on consumption of ketogenic diets. The issue here is not with protein intake per se but rather with saturated fat. Let’s be clear: you can have a high protein intake without consuming large amounts of dietary fat. They are not necessarily tied to one another. Lean poultry, fish and beef have a low fat content. So any discussion about cardiovascular issues should be relegated to dietary fat consumption irrespective of protein intake (and for the record, there is much dispute as to whether saturated fat actually plays a role in atherosclerosis – but that’s a topic for another day).

That out of the way, I’ll delve into the other areas of contention. In this post I’ll cover the effects of a high protein intake on kidney function. In Part II I’ll explore the impact on bone. Okay, let’s dig in.

The claim that a high protein intake is detrimental to the kidneys has been attributed to Dr. Barry Brenner, a physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. A little background is in order to understand the purported issues. The metabolism of protein entails a complex sequence of events for proper assimilation to take place. During digestion, protein is broken down into its component parts, the amino acids (via a process called deamination). A byproduct of this occurrence is the production of ammonia, a toxic substance, in the body. Ammonia, in turn, is rapidly converted into the relatively non-toxic substance urea in the liver, which is then transported to the kidneys for excretion. The excretory process initially takes place in an area of the kidneys called the glomerulus, where waste is filtered through a large network of capillaries.

Brenner proposed that the associated urea production from excessive protein intake overloads the glomerulus, thereby causing renal injury and dysfunction. This became known as the “Brenner Hypothesis.” Brenner’s work in the area was published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine and the hypothesis subsequently became gospel in academic nutritional circles.

Here’s the rub: Brenner’s hypothesis was based on data from animal studies and those with existing renal disease. And as any good scientist knows, you cannot necessarily extrapolate such results to a healthy population.

An examination of the literature shows that, within wide limits, there is no evidence that a diet high in protein has any detrimental effects on those with normal renal function. Healthy kidneys are readily able to filter out elevated amounts of urea. In a review of research, Martin et al. concluded that “we find no significant evidence for a detrimental effect of high protein intakes on kidney function in healthy persons after centuries of a high protein Western diet.” These findings are consistent with those in a review on the effect of high protein diets in an athletic population. Studies have examined protein intakes in excess of three times the RDA without noting ill-effect. And in case you want to argue that the negative effects of protein intake on renal function take a long time to manifest and thus may not be detectable in shorter-term studies, a recent study by Lowery et al. found no markers of renal damage over a nine-year period in a cohort of healthy resistance trained subjects who consumed an average of 2.5 g/kg/day. It should be noted that increased protein consumption does lead to increases in renal size over time. However, studies show that this is a normal adaptation that has no adverse effects on kidney function.

So how much is too much? It has been postulated by some researchers that an intake greater than ~4 to 5 g/kg/day may exceed the body’s ability to convert the excess nitrogen load to urea for safe excretion. Thus, a 165 pound male would theoretically fall into the safe range at anything up to about 300 g/day; a guy weighing 220 pounds would have an upper limit of ~400 g/day. That’s *a lot* of protein! In actuality, this recommendation is probably a bit conservative. A portion of the protein you consume does not require deamination since it is directly utilized for structural remodeling of bodily tissues as well as production of hormones, enzymes, and other functions. Thus, safe levels of intake conceivably would be somewhat higher than previously thought.

Bottom line: High protein intakes may be detrimental to those with existing renal dysfunction, but there is no evidence that any negative effects are seen in individuals with healthy kidneys. Consumption of up to approximately 4 g/kg/day appears to pose no increased health risk when kidney function is normal. It’s been well-demonstrated that resistance-trained individuals require at least twice the amount of protein compared to non-lifters (although the benefit of consuming more than ~2 g/kg remains questionable from an anabolism standpoint). Moreover, higher protein intakes are beneficial for fat loss, both in terms of promoting satiety as well as reducing muscle catabolism during times of caloric restriction.

Stay tuned for Part II where I’ll discuss the claim that high protein diets are harmful to bone.

Stay Fit!

Brad

July 20, 2013

M.A.X Muscle Warm-Up

Writing a book is a lengthy, arduous process. To do it right involves a great deal of planning. You need to map out everything that needs to be covered and decide on the best way to organize this information into a cohesive, readable format. A diligent author spends countless hours contemplating these complexities before a single word makes it to the page. But no matter how attentive you are to detail, there are always some things you somehow miss that ultimately become apparent once the book is released. The best you can do at this point is to address any omissions ex post facto.

Based on reader feedback and questions, it has come to light that I made such an omission in my book, The M.A.X. Muscle Plan, with respect to warming up prior to training. In retrospect, this is not something that I should have taken for granted. A warm-up heightens blood flow to muscles, enhances speed of nerve impulses, increases energy substrate delivery to working muscles as well oxygen release from hemoglobin and myoglobin, and reduces the activation of energy for cellular reactions and muscle viscosity (Thacker et al. 2004). Suffice to say, it’s an important component of a workout. This post therefore will seek to rectify the oversight and address my recommendedations for the M.A.X. Muscle warm-up.

A warm-up can be divided into two distinct components: general and specific. The general warm-up – which involves performing a brief bout of low-intensity, large muscle group aerobic-type exercise – should be included in all three M.A.X. Muscle mesocycles (i.e. strength, metabolic conditioning, and hypertrophy). The purpose of the general warm-up is to elevate core temperature and increase blood flow. This has implications not only for injury prevention, but for performance as well. In fact, there is evidence that combining a general warm-up with a specific warm-up increases maximal strength to a greater degree than peforming a specific warm-up alone (Abad et al. 2011).

Virtually any cardiovascular activity can be used for the general warm-up. Modalities such as the stationary bike, stair climber, or treadmill are fine, as are most calisthenic-type exercises (such as jumping jacks, high steps). Choose whatever activity you desire as long as the basic objective is met.

As previously noted, the intensity for the general warm-up should be low. To gauge intensity, I like to use a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale. My preference is the Category-Ratio RPE Scale, which grades perceived effort on a range of 0-10 (where 0 is lying on your couch and 10 is an all-out sprint). Aim for an RPE of around 5, which for most would be a moderate walk or slow jog. Five to ten minutes is all you need – just enough to break a light sweat. Your resources should not be taxed, nor should you feel tired or out of breath either during or after performance. If so, cut back on the intensity. Remember, the goal here is merely to warm your body tissues and accelerate blood flow — not to achieve cardiovascular benefits or reduce body fat.

The specific warm-up augments the general warm-up. It serves to enhance neuromuscular efficiency in performing a given exercise. To optimize benefits, the exercises used in the specific warm-up should be as similar as possible to the actual activities in the workout. For example, if you are going to perform a bench press, then the specific warm-up would ideally involve performance of light sets of bench presses. In this way, the neuromuscular system gets to “rehearse” the movement before it is performed higher levels of intensity. Specific warm-up sets should always be stopped well short of fatigue – the focus here is to facilitate performance of the heavier sets.

For the M.A.X Strength Phase, I recommend at least a couple of specific warm-up sets per exercise. Since this phase employs a total body routine with very heavy loads (>85% 1RM), it is important that each exercise include specific warm-up sets. As a general rule the first set should be performed at ~40-50% of 1RM and the second set at ~60-70% 1RM. Eight to ten reps is all that is needed in these sets –any more than this is superfluous. Thereafter, you’re then ready to plow into your working sets.

For the M.A.X Hypertrophy Phase, I recommend performing a specific warm-up prior to the first exercise for each muscle group only. Since this is a split-routine where multiple exercises are performed per body part, the benefits achieved from the specific warm-up on the intial movement will carry over to the other exercises for the subsequent exercises for that muscle group. Additional warm-up sets can actually be detrimental since they can hinder generation of metabolic stress, which is a desired outcome in this phase.

Specific warm-up sets are not necessary in the M.A.X Metabolic Phase. In this phase you’re already using light weights and the initial repetitions of each working set therefore serve as “rehearsal” reps. What’s more, performance of warm-up sets is counterproductive to the goal of maximizing training density to bring about desired metabolic adaptations.

Hopefully this addresses the feedback and questions I’ve received on the topic. I’ll look to cover some additional questions I’ve received in future posts. In the meantime, keep the comments coming!

Brad

References

-

- Abad CC, Prado ML, Ugrinowitsch C, Tricoli V, Barroso R. Combination of general and specific warm-ups improves leg-press one repetition maximum compared with specific warm-up in trained individuals. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Aug;25(8):2242-5.

- Thacker SB, Gilchrist J, Stroup DF, Kimsey CD Jr. The impact of stretching on sports injury risk: a systematic review of the literature. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004 Mar;36(3):371-8

July 1, 2013

Website Makeover

If you’re a regular reader of my blog, you’ll probably notice something different. Yep, I’ve taken the plunge and completely revamped my website. It had been six years since I last updated the site design. In the world of cyberspace that’s an eternity. I realized that it needed a makeover to keep up with the times.

The first thing you’ll see from the makeover is that my blog is now fully integrated into my primary site (www.lookgreatnaked.com). Sure, you can still access the blog by typing in Workout911.com. But now the blog and site are seamless in their navigation. The focus of the blog will remain the same; I’ll continue to strive to deliver quality content on fitness-related matters. The fact that I’m finishing up my PhD coursework should allow me more time to devote to posts.

The site itself is designed for functionality. In the “Articles” section I’ve posted the PDFs to many of my peer-reviewed papers as well as links to some of my online articles. I’ll continue to update this page more of my work becomes available. The site also has lots of other areas of interest. I’ve updated my bio and media kit, added testimonials, and revamped the products/services page. The site is an ongoing work-in-progress so I hope to enhance its utility over the coming months.

A big thanks to Michael Muff of White Buck Media for doing an outstanding job on the design and working tirelessly to make sure that the implementation was smooth and successful. I recommend him wholeheartedly for any web-related consulting.

Hope you enjoy the new site. I welcome any and all feedback that you may have. Just drop me a line.

Cheers!

Brad

June 9, 2013

This and That…

So much going on that I want to share. First, I just returned from my last semester of PhD coursework at Rocky Mountain University in beautiful Provo, Utah. The attainment of my doctoral degree is finally in sight! I am on schedule to begin data collection on my dissertation research later this summer and, if all goes according to plan, defend my dissertation in January. This has been an amazing–albeit grueling–educational journey. I’ve learned so much about critical thinking, met so many incredible people, and honed my skills as a researcher along the way these past two-and-a=half years. I’ll be blogging about my experience in the near future. Stay tuned…

So much going on that I want to share. First, I just returned from my last semester of PhD coursework at Rocky Mountain University in beautiful Provo, Utah. The attainment of my doctoral degree is finally in sight! I am on schedule to begin data collection on my dissertation research later this summer and, if all goes according to plan, defend my dissertation in January. This has been an amazing–albeit grueling–educational journey. I’ve learned so much about critical thinking, met so many incredible people, and honed my skills as a researcher along the way these past two-and-a=half years. I’ll be blogging about my experience in the near future. Stay tuned…

My review article, Postexercise hypertrophic adaptations: a reexamination of the hormone hypothesis and its applicability to resistance training program design has been published in the current issue of the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. The article exhaustively reviews the literature on whether acute hormonal elevations following resistance training play a role in muscle growth. For years, it was believed that spiking hormones after exercise was the key to maximizing hypertrophy. Entire workouts were planned around maximizing the anabolic hormonal response. Turns out, this belief was misguided. Studies are equivocal as to whether post-workout hormonal elevations are involved in the muscle-building process; some show a positive correlation, others do not. Bottom line is that if there is a hypertrophic effect from such elevations, it would be relatively modest. That said, even a modest effect on hypertrophy could be practically meaningful to someone seeking maximal muscle development, such as a bodybuilder or strength athlete. There are still many gaps in the literature that need to be sorted out before a definitive conclusion can me made on the topic–particularly with respect to the effects in experienced lifters. I will be carrying out research in the coming months that hopefully will help to fill in some of these gaps. Will keep you updated here when I have data to share.

I recently did two interviews of interest with Super Human Radio. The first, The Role of Metabolic Stress in Muscle Growth is an extensive discussion of various aspects of muscle hypertrophy. The second, Look Great Naked delves into women’s fitness as well as touching on post-workout nutrition. What I really like about these interviews is that the host, Carl Lanore, is a true science geek. As such, he let’s me expound on the science of these topics in depth. I go into a level of detail generally not afforded in other media outlets. Each interview lasts about an hour so there’s a lot of listening for your enjoyment 🙂

About a year or so ago I wrote an article on glute training that appeared in Fitness Rx for Women magazine. Well, lo and behold, they published the article online for free! The article is called, The Tight and Toned Butt Workout (yeah, I know the title is a bit cheesy, but hey, that’s apparently what sells magazines…). Although the article is geared toward women, it’s a routine that can be used effectively by men too. Check it out.

Book update: Rodale has acquired the mail order rights to my book, The M.A.X. Muscle Plan. In case you don’t know, Rodale is an industry leader in fitness media. They publish Men’s Health Magazine, as well as many other fitness publications. As I’ve mentioned previously, this book was the culmination of many years of of research and practice, and represents the most cutting-edge muscle building program ever developed (and I’m not blowing smoke when I say this!). It’s available at a discount on Amazon.com as well. I hope you’ll give it a read; I’d love to hear your feedback.

Finally and importantly, I have agreed to a consultant role with Reebok International. In my role, I will be providing educational content for fitness professionals as well as making select appearances at Reebok-sponsored events. There are other as-yet undefined areas that may be explored as well. I am honored to be affiliated with such a terrific brand and look forward to partnering with them to share my fitness expertise.

Finally and importantly, I have agreed to a consultant role with Reebok International. In my role, I will be providing educational content for fitness professionals as well as making select appearances at Reebok-sponsored events. There are other as-yet undefined areas that may be explored as well. I am honored to be affiliated with such a terrific brand and look forward to partnering with them to share my fitness expertise.

Stay Fit!

Brad

April 14, 2013

Hypertrophy Seminar in NYC

For those in the New York City area, I will be giving a 3-hour seminar next month on Advanced Programming for Muscle Hypertrophy. The seminar is being held at the American Academy of Personal Training, located in the meat-packing district of Manhattan, as part of their continuing education series. Here is the session description.

Muscle development is of primary interest to those who partake in resistance training. But developing muscle size, as opposed to strength or endurance, involves its own unique set of considerations. This AAPT course elucidates the science behind optimizing muscular hypertrophy, exploring how factors such as exercise modality, training to failure, speed of movement and recovery affect muscle growth. You will learn the significance of metabolic stress in relation to protein synthesis, as well as gain a trove of valuable techniques in manipulating intensity, sets, repetitions, and rest intervals. Sample routines will be provided in the context of a periodized approach to help you with perfecting program design for muscle hypertrophy.

The seminar will take an evidence-based approach, going in-depth into how to combine science and art in creating optimal hypertrophy training programs. Below is the link to register. Hope to see you there!

Advanced Programming for Muscle Hypertrophy

Brad

April 13, 2013

Q&A: Protein Requirements During Resistance Training

Hi Brad

I just bought your book “The Max Muscle Plan.” When I read about the different macro nutritions on the web I somehow end up a bit confused, the 2gr/kg body weight of something seems straight forward but then some talk about the lean body weight (without the fat) and some about total body weight (incl fat) and then I saw in your book (not sure what page as it is the kindle version) but it is under “What to eat after a workout” – you talk about ideal bodyweight, other places you just mention bodyweight.

I bet a lot of other people are a bit confused just like me about all the different measurements on the web, maybe you could post some bits and bobs about it on your workout911 it would be a great help.

Best regards and thank you

David,

Denmark

Hi David:

The focus on “ideal bodyweight” is simply a way to qualify that an overweight person does not need extra protein to support growth. As an extreme example, if you weigh 300 pounds at 50% body fat, there is no added benefit to consuming ~300 g/day of protein; the additional intake it’s not going to help you build more muscle. Curiously, however, the literature historically has historically reported protein requirements in terms of bodyweight without standarizing recommendations for percent body fat. Given that body composition of subjects varies from study to study, this makes it somewhat difficult to tease out the true lean tissue requirements for anabolism.

There is compelling evidence that those involved in resistance training need more protein than sedentary couch potatoes. This is not even debatable. So assuming you regularly lift weights (and if not, get with the program!) how much protein should you consume? There are a number of mitigating factors here. First and foremost is caloric intake: a caloric surplus (i.e. taking in more calories than you are expending) will reduce protein requirements, while a caloric deficit (taking in fewer calories than you are expending) will increase protein requirements (Mettler et al. 2010). Moreover, the protein needs for lean individuals in a caloric deficit will be higher than that of those who are overweight.

Gender also has an impact on protein requirements. Specifically, women are better able to preserve lean mass compared to men during times of reduced caloric intake (Lemon, 2000). This appears to be a survival mechanism related to maintenance of reproductive function. Bottom line is that men are more apt to lose muscle while dieting if protein consumption is low.

Of course, genetics will also enter into the equation. Research studies report the mean (i.e. average) value of all subjects in the trial. Some individuals will display greater needs while others not so much. Unless you are tested individually, there is no way to know your exact requirements.

Finally, there is some evidence that highly experienced lifters actually need *less* protein than those in the early stages of training (Phillips et al. 2007). It is theorized that well-trained individuals become more efficient at utilizing dietary proteins for tissue building, thereby reducing requirements. The validity of these findings remain to be determined.

With this as background, my general recommendation as outlined in The MAX Muscle Plan is to consume approximately 1 gram per pound of “ideal” bodyweight, which I subjectively qualify as being around a 10% body fat level. This is slightly above the generally prescribed levels necessary to maintain a non-negative protein balance in resistance-trained individuals (Kersick et al. 2008). My reasoning is to provide a margin of safety. An insurance policy, if you will. IMO, there is a good cost/benefit ratio to such an approach: keeping protein intake a little higher *might* confer an anabolic advantage depending on some of the previously mentioned factors; at worst you’ll simply oxidize the extra protein for energy (assuming total caloric intake remains constant).

And in case anyone thinks that consuming higher protein will damage your kidneys or bones, think again. Provided that you are otherwise healthy, studies show no negative effects on renal function (Martin et al. 2005; Poortmans and Dellalieux, 2000) or bone health (Bonjour, 2005).

Hope this helps. Cheers!

Brad

1. Bonjour JP. Dietary protein: an essential nutrient for bone health. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005 Dec;24(6 Suppl):526S-36S.

2. Kerksick C, Harvey T, Stout J, Campbell B, Wilborn C, Kreider R, Kalman D, Ziegenfuss T, Lopez H, Landis J, Ivy JL, Antonio J. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: nutrient timing. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2008 Oct 3;5:17

3. Lemon PW. Beyond the zone: protein needs of active individuals. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000 Oct;19(5 Suppl):513S-521S.

4. Martin WF, Armstrong LE, Rodriguez NR. (2005). Dietary protein intake and renal function. Nutr Metab (Lond). 20;2:25

5. Mettler S, Mitchell N, Tipton KD. Increased protein intake reduces lean body mass loss during weight loss in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Feb;42(2):326-37

6. Phillips SM, Moore DR, Tang JE. A critical examination of dietary protein requirements, benefits, and excesses in athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2007 Aug;17 Suppl:S58-76.

7. Poortmans JR, Dellalieux O. (2000). Do regular high protein diets have potential health risks on kidney function in athletes? Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 10(1):28-38

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)