August 23, 2015

A Better Way to Gauge Intensity of Effort During Resistance Training

In a recent interview for The Fitcast, the host asked whether there was anything I’d change about my book The MAX Muscle Plan. A fair question, no doubt. After all, the book was written over four years ago and our understanding of the science and practice of training continues to evolve. So naturally there were several things that I mentioned in retrospect, most pertinently my views on nutrient timing.

But afterward, it occurred to me that I neglected to bring up an important topic of concern; namely, my use of the ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) scale to gauge training intensity of effort. Now don’t get me wrong; the RPE is a viable tool in this regard. Research shows that It provides a reasonably accurate means to predict 1-RM from submaximal lifting intensities. Fitness professionals have used it extensively for years.

That said, previous research found a mismatch between RPE and max effort during sets to failure. A subsequent study showed similar discrepancies.

The literature backs up my personal experience on the topic. Since publication of my book, I’ve received a number of emails from readers saying they were confused about the use of the scale. Some stated they found it awkward to integrate into practice. Others felt that terms such as ‘moderate’ ‘hard’ and ‘extremely hard’ were too ambiguous with respect to exercise intensity of effort.

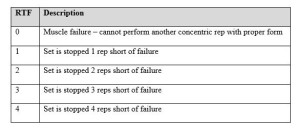

Fortunately, I’ve since come to learn that a more intuitive scale called Reps-to-Failure (RTF) exists. As the name implies, the RTF is based on how many reps you perceive you have left in the tank after completing a set. If you went to all-out failure, the value would be ‘O’ (no reps left in the tank). If you feel you could have gotten an additional rep, the value would be 1; if you could have gotten 2 additional reps you’d be at a ‘2’, etc. I limit the range from 0-4; anything above a 4 is basically a warm-up set. Below is a chart that outlines the particulars of the scale.

The RTF scale has been validated by research. A recent study of competitive male bodybuilders showed a high positive association between estimated RTF and the actual number of repetitions-to-failure achieved. Accuracy was found to improve during the later sets of exercise performance, indicating a rapid learning curve the more the scale is used.

So my recommendation here is to use the RTF scale for gauging lifting intensity; IMO, it’s easier to employ and more accurate than the RPE. If you’re currently using The MAX Muscle Plan simply substitute the RTF value for the RPE in reverse order. Thus, an RTF of ‘0’ corresponds to an RPE of ’10’; an RTF of ‘1’ corresponds to an RPE of ‘9’, etc. It shouldn’t take you more than a few sessions experimenting with the RTF to be thoroughly proficient in its use.

9 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)

Thanks for the update!

Comment by Greg — August 23, 2015 @ 11:27 pm

[…] ever wondered what light, moderate, or heavy intensity means when weight lifting? I found this article interesting and thought we might want to employ it during our strength training. What do you […]

Pingback by CrossFitSL | Intensity Gauge - CrossFitSL — August 24, 2015 @ 11:48 pm

[…] revealed in a beginner training log, but using RPE‘s or Brad Schoenfeld’s new Reps-to-Failure can give you a more mindful approach. Experimenting with how we track our training can be key to […]

Pingback by So How Do You Measure? | Harold Gibbons — September 3, 2015 @ 6:25 pm

Hey Brad,

I just wanted to say thanks for writing and updating such a great book. Whenever your name is mentioned in an article, blog post or podcast, the first thing I do is jump right to it.

Keep up the great work, and I do have questions: What’s next for hypertrophy and your next book? What’s the next big thing in your opinion? What are your views on high frequency and DUP for growing in a year’s macrocycle?

Comment by Chris — September 8, 2015 @ 7:17 pm

Great post. I have been using RPE for myself as well as clients, and I have always thought it might be a bit confusing since I know many of my clients train alone, and if I were to give them an RPE 10 I wouldn’t want them to actually reach concentric failure but rather relay the idea of 0 reps to failure, so I quite possibly may switch to using RTF when I write my programs.

Comment by Brian — September 11, 2015 @ 1:05 am

I’ve been implementing RPE as a staple for determining training loads but I found this extremely beneficial and more logical. I will begin utilizing it immediately. Thanks Brad.

Comment by charles donahue — September 25, 2015 @ 7:46 am

Why not just have Repetition maximums? It’s seems like a waste of time to have this system. I would say t do sets where you reach technical failure.

Comment by Marcus Beasley — November 18, 2015 @ 2:44 pm

This is just what I used to do as a kid working out. Because I usually worked out alone at home, I couldn’t depend on someone helping me lift the barbell off of my chest or neck for that matter. First a warm set with a light weight. Then, when I got a feel for the weight I wanted to work with, my second set, I performed half a set, not even close to failure. Then after resting, I proceeded to do my 3rd set 4 or 3 reps shy of failure. Finally, the last set was 1 or 2 reps close to failure.

Working within technical failure, or better yet until the reps slowed down, added an extra layer of safety to make sure I didn’t get pinned under the bar. And I don’t think I was alone. I think most kids working out in their basements or garages had developed the same system, just to avoid killing ourselves. So I’m glad someone gave it a name, although I’m sure I heard Norton refer to RIR, Reps In Reserve on one of his episodes a few weeks ago.

The thing is, back then I never logged my workouts, and almost blindfully worked out to feel, and I did all right. But recently, when trying to implement RPE, I noticed I can’t judge it and retain the amount of reps I just did. I’m huffing and puffing, got blood racing through my head and flooding my muscles, got in mind the weight I’m using in mind, and sometimes the next weight I’m about to use, the rep range I should hit, which set it is … well this is all too much info to think about when pushing iron. My main issue seems to be that I confuse the RPE with the amount of reps performed, since they’re both numbers. I’ve recently thought maybe a letter based RPE could avoid consuing the two.

Then I ask myself, What’s the point? If I’ve decided on a weight that’ll leave me within a certain rep range, say 8-12 and if it’s too heavy I simply won’t make the rep range –assuming I’m not step-loading and using normal progression. And considering I’m keeping track of good reps, shouldn’t this be enough to provide bio-feedback on fatigue and/or over-reaching so as let me know when to change the current block?

Comment by mo — December 29, 2015 @ 8:57 pm

Ok, I’ve pondered on your book Brad, and realized that you don’t seem to mention rep ranges at all; so, your system uses RPE as a gauge equivilent to what rep range can serve as in a double progression scheme (make sure you’re hitting the correct intensity range). I’m still hangging onto remnants of double progression.

I’ve realized rep ranges as used in the double progression manner are useless with step-loading, considering step-loading uses percentages to work up to the RM being used (15RM, 10RM, or what not). So what happens with step loading is that you tend to get a higher rep volume in the early micro-cycles of a block, while working oneself back up to the RM being worked — making the traditional rep range useless as an intensity gauge.

A few questions arise.

Should one not be able to use a variable target rep for each stage in the step-loading progression?

Something like this?

14 reps for 75% of 9RM

13 reps for 80% of 9RM

12 reps for 85% of 9RM

11 reps for 90% of 9RM

10 reps for 95% of 9RM

9 reps for 100% of 9RM (the last workout before deloading)

So that takes care of using a target rep with step-loading.

I also have major concerns about the feasibility of step-loading for hypertrophy, but this comment is getting way too long. Perhaps, I’ll write a blog post and invite you Brad to comment on it.

Comment by mo — December 31, 2015 @ 12:40 pm